Anatomy of the Long Tail

I admit I’m a movie snob. I’m less likely to watch blockbusters about toys gone wild that open on 4000+ screens than tales of food gone wild that open on 50 screens. And for this I always figured I was among a minority who ventured beyond the standard Hollywood fare. Well, it turns out that it’s pretty ordinary to have extraordinary tastes. In a study of consumer preferences across movies, music, web browsing, and web search, Andrei Broder, Evgeniy Gabrilovich, Bo Pang, and I find that nearly everyone is a little bit eccentric.

The explosion of electronic commerce has opened the door to infinite-inventory retailers, such as Amazon and Netflix, that offer an order of magnitude more items than their brick-and-mortar counterparts. These so-called “Long Tail” markets, as coined by Chris Anderson, have been found to exhibit two near-universal properties: First, the vast majority of products are “misses,” appealing to only a relatively small group of people; and second, these “worst-sellers” in aggregate account for a sizable fraction of total consumption. For example, 30% of Amazon’s sales and 25% of Netflix’s sales are for items not available in the largest offline retail stores. Based on these empirical observations, the success of online retailers has been largely attributed to the lucrative, and previously untapped, market for niche items.

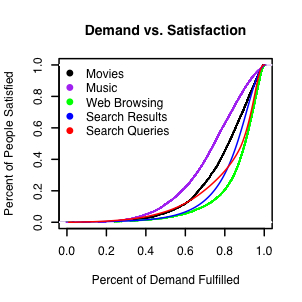

The long tail phenomenon, though, is in principle consistent with two fundamentally different hypotheses. The conventional wisdom is that most people exclusively consume popular offerings, with only a minority seeking out niche content. However, a second hypothesis is that everyone is a little eccentric, consuming both popular and specialty products. Importantly, these two theories predict substantively different consequences of inventory size on consumer satisfaction. In the former case, a small inventory of high-demand items would satisfy most people nearly all of the time, while in the latter, such an inventory would frustrate most people at least some of the time.

We find overwhelming evidence that nearly everyone is at least a bit eccentric. For example, 85% of Netflix users and 95% of Yahoo! Music users have ventured into the tail (i.e., consumed items not available in large, brick-and-mortar retailers), and 40% of Netflix users and 70% of Yahoo! Music users regularly consume tail items. Our results thus suggest an additional factor for the success of infinite-inventory retailers. Tail inventory may boost head sales by offering consumers the convenience of “one-stop shopping” for both their mainstream and niche interests. Hence, even small increases in direct revenue from niche products may be associated with much larger second-order gains due to increased overall consumer satisfaction and resulting repeat patronage.

One can see this second-order effect by examining the relationship, as inventory size increases, between the percent of demand fulfilled and the percent of consumers satisfied. Stocking more items naturally leads to selling more items (i.e., the first-order effect of directly fulfilling demand). What the plot above indicates, however, is that increases in direct revenue come with disproportionate increases in consumer satisfaction. Consequently, to the extent that increased inventory attracts new customers, direct revenue calculations undervalue the tail. In particular, when deciding whether or not to stock the latest worst-seller, the pertinent question is not, How many copies will I sell?, but rather How many customers will I gain?.

So people aren’t sheep after all. That’s probably a good thing, but it makes it a whole lot harder to run a video store.

N.B. For more details, check out our paper or these slides from a talk I gave at NYU. Anita Elberse also discusses related findings in her Harvard Business Review article, Should You Invest in the Long Tail?.

Illustration: Kelly Savage