Popping the Filter Bubble

In his provocative TED talk and bestselling book, the progressive internet activist Eli Pariser tells the story of how one day he noticed that the Facebook posts from his politically conservative friends began disappearing from his newsfeed. Pariser traces this phenomenon back to Facebook’s recommendation algorithms, which looked at the links he clicked, effectively learned his left-leaning preferences, and accordingly tailored the content presented to him. He goes on to argue that such invisible and insidious personalization creates filter bubbles that narrow our worldview, increase ideological segregation, and threaten the foundations of democracy. Pariser is not the only one sounding the alarm. Cass Sunstein, the prominent Harvard Law School professor, also laments the rise of personalization, warning that with customized Facebook feeds, Netflix recommendations, and web search results, society is in danger of fragmenting.

On its surface, the filter bubble theory is compelling. Not only are the arguments by Pariser, Sunstein, and others intuitive and persuasive, a variety of laboratory studies also support the contention.[1] However, perhaps surprisingly, political polarization in the general U.S. population has been relatively stable for the last several decades,[2] and a casual perusal of popular news sites does not reveal a substantial proportion of niche or extreme political content. We are therefore left with a puzzle: How do we reconcile the considerable evidence that suggests current online conditions should promote ideological segregation with the apparent lack of significant fragmentation?

Seth Flaxman, Justin Rao, and I recently studied this apparent paradox by examining the online news reading habits of 1.2 million (anonymized) individuals, for whom we had a nearly complete record of the webpages they visited during a three-month period earlier this year. To measure ideological segregation, we first estimated the conservative share of the most popular news sites, defined to be the fraction of each website’s audience that voted for the Republican candidate in the last presidential election. In line with previous rankings, we find that the list ranges from BBC and The New York Times on the left, to Fox News and Newsmax on the right. We then measure ideological segregation by computing the average difference in the conservative shares of news outlets visited by two randomly selected individuals. Larger values of this measure indicate that the population is more segregated.

“Though our results are directionally consistent with filter bubble fears, the relative dearth of news stories shared on social media mitigates the overall effect.”

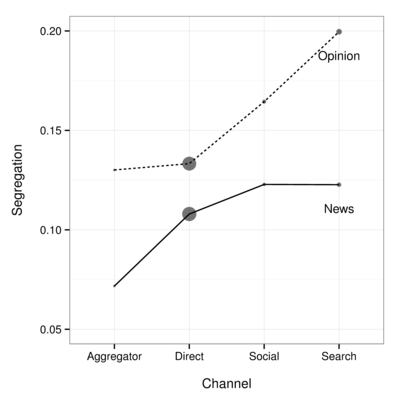

The plot below shows estimates of online segregation, computed separately for descriptive news and opinion articles, and also for various consumption channels: aggregators (e.g., Google News), direct browsing (i.e., an individual directly navigating to the news site), social media (e.g., Facebook and Twitter), and web search.[3] Consistent with filter bubble fears, we find that individuals indeed exhibit higher segregation when reading news articles shared on social media or returned by search engines, a pattern driven by opinion pieces. However, as indicated by the sizes of the points, these polarizing opinion articles from social media and web search constitute only 2% of total news consumption, with individuals getting the vast majority of their online news by directly visiting their favorite sites. As a consequence, the overall level of segregation is relatively moderate (0.11), approximately corresponding to the ideological distance between USA Today and The Washington Post. Thus, though our results are directionally consistent with worries that personalization spurs ideological segregation, the relative dearth of news stories shared on social media or returned by search engines mitigates the overall filter bubble effect.[4]

To be clear, just because this recent wave of personalization has not fractured society, that does not mean that political discourse is thriving online. In particular, we find that most individuals only rarely read articles from the opposite side of their preferred partisan perspective. This echo chamber, however, is not a consequence of algorithmic or implicit customization, but rather results from individuals actively seeking out ideologically similar news sources.

As to why online social networks are not a dominant means for distributing news, perhaps it’s because people prefer to use Facebook to share pictures of babies and puppies rather than to engage in serious political debate. Or perhaps it’s because Justin Bieber takes better selfies than Glenn Beck. Regardless, the net effect is that while the technological ingredients for ideological fragmentation are in place — and indeed impact consumption — the detrimental consequences of the filter bubble appear to have thus far been largely avoided. So at least for now we can’t blame the end of the world on Facebook.

For further details, see our forthcoming paper, Ideological Segregation and the Effects of Social Media on News Consumption.

Illustration by Kelly Savage

Footnotes

[1] See our paper for a review of the literature.

[2] By contrast, political parties have become more partisan.

[3] We restrict our analysis to articles that would typically appear in the front-section of a traditional newspaper, and in particular, we explicitly filter out sports, entertainment, weather and other topics for which ideological segregation is less meaningful.

[4] Personalization on social media results from a combination of algorithmic filtering, the relative similarity of social contacts, and explicit decisions to follow like-minded individuals.